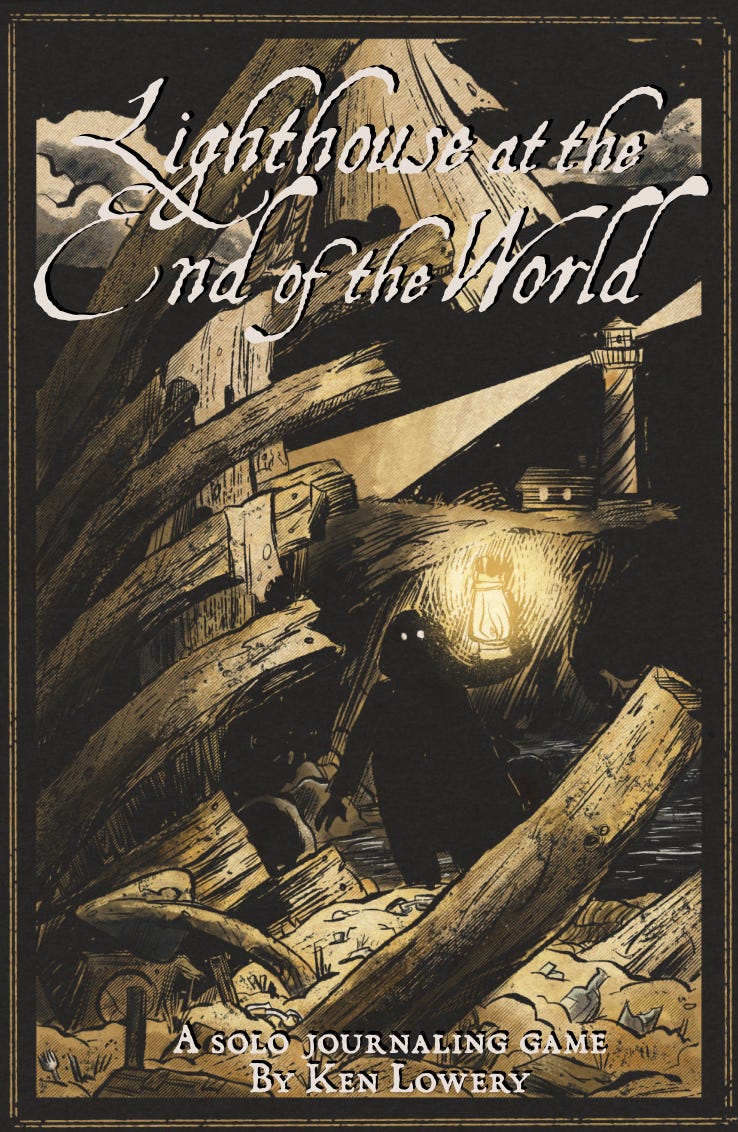

Lighthouse at the End of the World: Part IV

“And the silence was old with waiting.” — Algernon Blackwood, The Listener

Welcome to Tabletop Journal Thursdays! A place to explore solo tabletop RPGs—not just the mechanics, but the stories they inspire and the worlds they build.

Each month, I’ll highlight a different game, journal through it, and reflect on the experience. In the pregame player Gregory Adams answers questions from LLM Agent G. G. Weir about the game and his experiences journaling a playthrough.

This time, we’re secluding with Lighthouse at the End of the World by Ken Lowery—a solo RPG ghosts, isolation and possible madness.

Published by Bannerless Games and available through https://bannerlessgames.itch.io/lighthouse, Lighthouse at the End of the World casts the player not as a hero or villain, but as a solitary lighthouse keeper posted at the furthest reaches of civilization—cut off from the world, beset by ghosts, and slowly unraveling.

Journal of Gideon Hart, Keeper, August Fountain Light, Thunder Bay, Lake Superior

The sun is shining, and I’m getting a spectacular autumn breeze from the south coming in across the lake. I can almost smell the apple pie and apple cider they must be enjoying in Michigan, getting the kids ready for Halloween.

Well, I’m here for an act that many would consider to be cowardice—about to make a list of ghosts I’ve met and finding that doing so requires as much courage as I can muster.

I’m not entirely sure about my mental state today, or how things are going to be for me moving forward. Three days have passed since the strange events, and since it rained yesterday—washing away much of the duckshit—it’s almost as if it never happened. Some helpful scavengers even came along and took the bodies of the fish-eating ducks killed in whatever that was

I haven’t been back in the office since then. I just can’t bring myself to go in there. The keeper’s office can go on without me, because I’ve taken all the journals out of there—both the recordkeeping I’m responsible for and the records of the previous keepers—and moved them into the living quarters so I can pore over them. And I guess it’s overdue that I relate my discoveries.

The journals begin thirty years ago with Kleb, who I’ve already met. Kleb served a keeper here as a young man; the ghost I saw was in his mid-50s. So Kleb probably didn’t die here—or, if he did, things are even stranger than I expect them to be. And I expect them to be pretty strange.

Kleb’s notes reveal that he had been playing chess with the penal-colony warden, a man named Colonel Galloway, using a telegraph. There was no phone or radio communication then. Maybe that’s not so unusual in the 1930s. I certainly have radio now, although I haven’t particularly found a use for it except to talk to shipping, and that is usually pretty dry. Probably my own fault, as I don’t have anyone to talk to.

Moving on—let the record show that Colonel Galloway was playing chess with the future Major Kleb in 1933.

I did locate the telegraph machine. It’s essentially a ticker-tape machine but instead of numbers and percentages it spits out ribbons of dots and dashes. It stuffed into a crate with about a hundred kilometers of its own output, just meters and meters of a thin but strong paper, gray and slick from whatever additives give it the right quality for smooth feeding. Some are labeled by the keeper who received the messages and this helps me understand when the others were received, as the gray of the paper becomes darker with age.

I can see where it is to be hooked up in the radio room, terminals that would provide power and signal if they weren’t clearly disconnected relics.

Kleb was here for only a year. His keeper’s log reveals a man who was meticulous and focused and who never missed an entry. Not much here in the way of journal or diary writing, although he did fill margins with little drawings. There are all kinds of ducks and other birds—but so clumsily rendered as to be nearer to glyphs than illustrations. Standouts are more than a dozen Canadian flags and army insignia. That’s all I have, really, to connect the Kleb who made these journals and the Kleb I saw last week.

The journal Kleb used is interesting. Kind of a flimsy white pasteboard cover with an embossed maple leaf and a gold blob that’s likely meant to be the stylized whale depicted more clearly on other manuals. The cover has warped over the years, probably from moisture. That Kleb’s journal even survived thirty years means it hasn’t seen excessive use. I wonder if anyone has ever looked at these journals besides other keepers.

Looks like the Coast Guard decided white was a bad color, because the next one—or I should say the next five—are all the same. Because after Kleb, we get a lifer. Or at least somebody who was here for almost two decades, crazy as that sounds.

Kleb was a local for sure, but Harold Hayes was a positive fixture. Twenty entries, three times a day, seven days a week for about seventeen years. That’s about 22,000 trips up the steps to wind the light. He missed a day here and there—easy to find because his entries are brief, his handwriting distinct, as is his signature: two capital H’s that look like a quartet of columns or a hastily drawn bridge.

So someone from the parks service or the shore patrol covered for H.H.—I can tell right away just by scanning.

An irony emerges, because H.H. is a bit more verbose, and I learned some about his experiences here. He talked about the ducks. He talks about playing chess with the Colonel, although I don’t find long, drawn-out records of the moves as I see in later journals. He talks about the red light that he will sometimes see in the topmost room, but he doesn’t say much more about it.

He’s got several poetic phrases for it, mostly feminine. I always heard ships were women. Lighthouses should probably be men. In any case, when she’s stuffed full of memory, as he likes to put it, the red light comes over her, and never fails to make HH sad—which is such an odd reaction to an inexplicable phenomenon that could also be a hazard to shipping.

After H.H. hands over to Walter Mercer. At last, here’s someone who writes more about himself than the lighthouse. I mean, sure, I’m doing that, but this is my own journal. I’m not going to put this in the official Coast Guard lighthouse logbook.

Walter was in the Coast Guard, and stationed here as part of his term of service. although he didn’t seem very diligent. He wasn’t a sailor, at least not by the standards I imagine his superiors would have held him to. Walter seemed pretty tightly wound too. He played chess with the Colonel, and I think had a bad habit of chewing on the pieces, because he said he was going to replace the chess set when he left.

I don’t know what he looked like, so the image I have is of a young man, probably ten years older than me, sitting in this cinder-block box of a radio room, decoding Morse code tape, absent-mindedly chewing on a white queen he lost four moves in. It absolutely cannot look like him.

I began to think he might still be alive. From what I’ve experienced. it appears that Walter joined the army and was sent to the Congo. Walter isn’t haunting the lighthouse. The Belgian soldier Walter shot is.

It’s when I write things like that that I’m so glad I’m putting this in my own journal and not in an official Coast Guard lighthouse logbook.

Walter Mercer was here for two years. His records are spotty. The light seemed to wind itself—that was something he was aware of. He chewed up the chess pieces. He saw the red light. And that’s all I know.

Walter followed by Douglas Perrin, ornithologist—the one who simply vanished. The only reason I can say that he didn’t die in one of these many crevasses is that the journal is here. I mean, he certainly would have taken it with him. It is that kind of book—a field book. It says “Field Book” right below the Coast Guard insignia. But there’s all the other evidence.

Perrin wouldn’t have run, as the Old Salt who serves as my supplier suggests, because he would have taken the book with him then too.

If he was invited to play chess, he doesn’t mention it. He delighted in the way the crank would operate itself, and this drove him crazy. Well, he figured there was some type of engineering inconsistency, and I can tell he was pressing the pen down pretty hard when he wrote about it.

He saw the red light—only twice that he specifically calls out—and he saw it from outside, which I’m surprised to say I envy. It’s also a comfort that, unlike H.H., Perrin had the sense to be unsettled by the sight of it.

Strange phantasmagorias settle over the lighthouse at certain times, perhaps the manifestation of the northern lights. The structure seems to redden in a glow of such brilliance and depth of shade it could be a threat to navigation.

Again, my lack of skill as a draftsman makes me incapable of transcribing or recording what I see here—moments from certain angles when this red haze shapes the lighthouse into the appearance of a woman in a plain, narrow skirt, very suggestive of colonial times. Down to the cap of the house, which takes on the appearance of a chronicle bonnet. And of course, this leaves the light itself as her face—and that is where the red is most pronounced, most clearly distorted, as it seems to swirl and bubble, as if it is not so much light as a dark red core being pressed and mutilated in an unkind fashion.

Perrin adds one more note. He did stay up to see the crank cranking itself, but he never witnessed that—it didn’t function. He said the lights went black, which shouldn’t happen. The chain can extend and the light will stop turning, but the light won’t go out. The two systems aren’t connected: one burns gas, one is a weight-driven gear system.

It’s odd, though. He doesn’t say the light went out. He says the room goes black, and he repeats this that a few times. A man as precise as Douglas Perrin wouldn’t say one thing when he meant another.

He doesn’t explore the contradiction, but there is one. He doesn't proclaim that it gets dark. He says something quite different.

The room goes black.

To be continued next week! I don’t know how many episodes this will be- ‘pantsing’ this one as they say.

Thank You for Reading