Welcome to Tabletop Journal Thursdays! A place to explore solo tabletop RPGs—not just the mechanics, but the stories they inspire and the worlds they build.

Each month, I’ll highlight a different game, journal through it, and reflect on the experience. In the pregame player Gregory Adams answers questions from LLM Agent G. G. Weir about the game and his experiences journaling a playthrough.

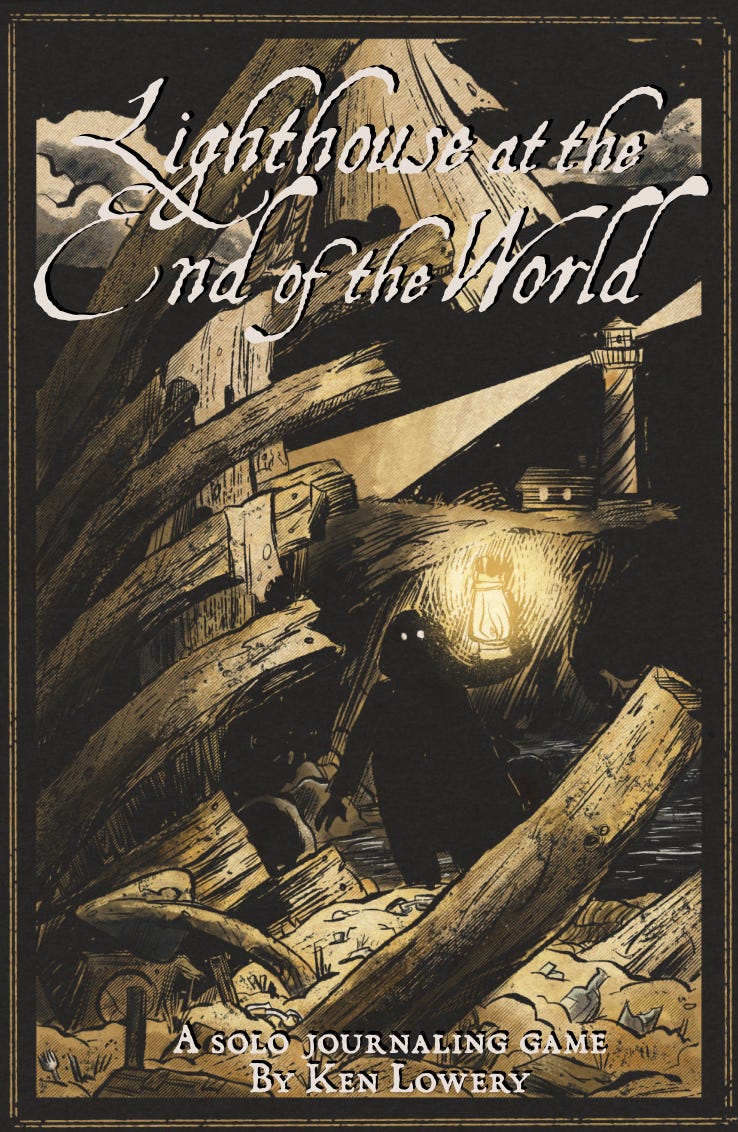

This time, we’re secluding with Lighthouse at the End of the World by Ken Lowery—a solo RPG ghosts, isolation and possible madness.

Published by Bannerless Games and available through https://bannerlessgames.itch.io/lighthouse, Lighthouse at the End of the World casts the player not as a hero or villain, but as a solitary lighthouse keeper posted at the furthest reaches of civilization—cut off from the world, beset by ghosts, and slowly unraveling.

“The houses seem asleep, and yet through every pane the watchful dead look out.”

— Thomas Gray (attributed), Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard

Journal of Gideon Hart, Keeper, August Fountain Light, Lake Superior

This only feels like the end of the world. It is Lake Superior. If the Earth were shaped differently, I could see the United States from here, dead south. As it is, all the land I can see is Canadian—land of the free to me and so many others who made President Soderberg's enemies list. The United States is the prison that I cannot enter; the rest of the world lies open to me, save for territories and holdings where the warrants for deserters would be enforceable. I have a perverse interest in traveling to Africa, where they wanted to send me as a soldier, but as a free man—a criminal—I know that I will never go there. I can talk all I wish about the courage it took me to flee the draft and avoid fighting fellow humans who never did me any harm, but there is a rich vein of cowardice in the strata of my emotions, and it is not deeply buried.

Beautiful day today, perfect August weather. I am writing this as I lean on the catwalk railing atop the Fountain Island lighthouse, called August Fountain, where “August” means grandiose or dignified, not the month, nor the ancient Roman emperor. The man who dropped me off here explained the name to me—“Grand island of many springs” is what it means—and this itself would mean something if the island were in a saltwater sea instead of a freshwater lake.

The cliffs, hidden rocks, and overall jagged character of this place warranted the lighthouse as a means to protect shipping traffic, but also meant the old fort had to be built on nearby Stewart Island. Stewart named this island, I'm told. The fort is still there, but it is a fort no more: it is a Canadian penal colony, and some of the stone walls and tall, barbed-wire-topped fences are visible to me from where I stand, the bulk of the structure hidden behind the aforementioned rock formations.

While not part of my official duties, I've been instructed to shoot anyone who comes over from my nearest neighboring island. No one told me where the gun is, however. Maybe I was supposed to bring my own. I took a good look in all the materials stacked throughout this lighthouse and the residence and found no gun. My search was meticulous and thoroughly catalogued. My ambition was to be a journalist, and although I wasn’t able to keep up with tuition or grade averages, I in no way lacked focus or obsession. I suspect that had I fulfilled my obligations, I'd be a quartermaster or even a combat correspondent in the Congo right now.

Instead, I am in a lighthouse, meaninglessly journaling while looking out over a lake that looks like an ocean, a criminal not in the penal colony, a wanted man who broke no law, on an island named neither for the month nor the tyrant.

Of course the lighthouse is haunted. Have I said that yet?

There is quite a bit of material I uncovered in sifting through all the detritus and outright junk that this place has become a sort of filter to capture from shipwrecks, from previous keepers, from whatever washes ashore. The keepers—who I’ll get into more later—seem to vanish or at least not serve out their terms in a typical way, a trend I hope to break for obvious reasons. It’s probably why they were so eager to hire me, even though I made it clear that I was a deserter. But Canada’s relationship with the United States isn’t the old gray mare it used to be.

But enough digression; let’s talk about the ghost.

I saw him my first night here. The lighthouse has electricity, but it’s not used to power the turn or light of the lantern because it’s so unreliable. The electricity fails in most every storm as the underwater cable is tossed about by the current, which is when ships rely on it the most. Therefore the light has a propane tank that gets filled every two weeks or so, and it’s mostly hands-off.

The carousel is different. Keepers are entrusted to climb the steps and wind it like a grandfather clock: weights descend, timed by a tangle of gears, which keepers must oil. My schedule is to wind it at 8 in the morning, 4 in the afternoon, and then close to midnight. This is the greater part of my responsibilities. Wind the carousel every eight hours, polish the brass, sweep the steps, try to keep the bird-droppings off the glass panes—and other than that, not too much else to do.

Midnight on my first day, still excited and unsettled by first-day jitters, I was climbing the metal stairs and there, in the doorway to the office, stood a man: in his fifties, white-haired, disheveled, weary, perplexed as he was perplexing. It would have been near to impossible for him to have made his way into the lighthouse without my knowing. Not only did I keep the doors locked, thanks to the meal my imagination was making of the nearby penal colony, but the lighthouse is sixty years old and punished by brutal winters seven months of the year. Every hinge creaked, every board groaned.

He looked right at me. He was in a modern uniform of the Canadian Air Force. There was snow on his shoulders and the tops of his tightly laced boots.

“I’m dreaming,” he said.

I didn’t scream or cry or lash out. I kept the light high and let it fill his face. He neither looked away nor blinked. His pupils did not contract. A patch on his filthy parka read “KLEB.”

Behind him, the small keeper’s office was filled with bright, arctic sunlight, white as a gull’s wing, far too much light to have come in through the small window and its thick, cloudy glass on even the sunniest day. This invasive, impossible light was distinct from the somehow synthetic glare of the enormous Mazda lamp turning just above our heads. The light was also unchanging, where any light that bled in from the bulb would have shifted and rolled across the floor. The artificial light did move in such a way, as my eyes picked this paler, plasticine glow from beneath the polar dazzle. The light surrounding this man was so bright I would have been blinded, had it been real, but it couldn’t be real.

“It’s haunted,” he said. “The lighthouse. Do you know that?”

Crunch crunch crunch came the sound from less than twenty steps above me. Someone was winding the gears, raising the weights that kept the light turning. I turned away and watched the chain ascend.

When I looked back to the office, the light—and the major—were gone.

It was twenty stairs to the lantern room and I made it in panicked steps, where I discovered no one and nothing out of place, just the chain winched snugly to the top, and the room filled a strange, somehow fecund odor of rot and seagull shit.

To be continued next week! I don’t know how many episodes this will be- ‘pantsing’ this one as they say.

Thank You for Reading